19

Jul 2019

Hospital violence: We can reduce it

Published in General on July 19, 2019

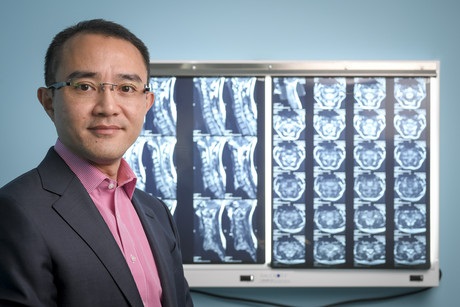

On a regular, mundane work day in Footscray, Victoria, doctor Micheal Wong hurried through the main doors and made a beeline for the foyer of Western Hospital.

As a full-time staff member, beloved neurosurgeon, and well-known local spinal surgeon, he was carrying a large workload and more than ready to get to work.

As the hospital was busy as usual, he felt safe as he usually did in his place of work. However, within a few split seconds, a patient ambushed him, pulling a knife. He was stabbed repeatedly. Those who witnessed the event sprang into action, fueled by shock.

The attacker was accosted with a handbag and a small sign that had been in the foyer, which momentarily slowed him down. Bystanders were able to pull Dr. Wong through the doors of the emergency department and into safety.

Upon inspection, it was found that the doctor had suffered 14 wounds: in the arms, chest, back, legs, abdomen, and forehead.

(Wounds to Dr Wong's hands from the attack)

Undergoing almost 12 hours of surgery with attention from multiple departments of surgeons including colorectal, cardiothoracic, plastic, and spinal, Dr. Wong was dubbed a survivor.

During the operation, his lung had been partially taken out to stem profuse bleeding that had resulted in the outcome of a particularly deep wound in his back.

(A deep wound to Dr Wong's back resulted in a partial lung removal.)

This wound had contributed to Wong losing his entire body’s blood volume during the procedure.

Poor security

Wong didn’t recognise the patient who attacked him. Later, he discovered that he had been part of the team tasked with taking care of the patient. The patient suffered poorly handled schizophrenia, which was the motivating factor of the attack.

When Wong was asked what we recommended for preventing similar violent attacks, his answer was direct and clear.

He stated that hospitals simply need to reduce the number of public-accessible areas and boost security in those areas.

“Why do we have so many publicly accessible areas in a hospital? It makes no sense,” Wong said. “In most hospitals, the general public can walk through the foyer, take a lift and walk to a patient’s bedside without being stopped.”

Dr. Wong and surely many others who witnessed the attack believe that patient wards and other important areas should be closed to the public. In addition, the doors to access said areas should be accessible via key cards held by staff, with family and friends of residing patients having the ability to ring a doorbell to gain access.

Security guards, he says, should be stationed permanently in public areas.

“When do you ever see security in the foyer of any hospital?” he asked.

Most hospitals employ a security guard station in the emergency departments of the establishment, as the emergency department is prone to seeing violent, drunk, and/or otherwise questionable patients. However, other areas of the hospital are left unguarded.

Thinking back, Wong was able to recall another incident: the case of Dr. Patrick Pritzwald-Stegmann of Victoria’s Box Hill Hospital. The accident took place in 2017 and Pritzwald-Stegmann died of his injuries, the killing blow said to be a punch from his attacker.

Having dedicated security guards in these areas could easily prevent similar attacks, he says. Had it not deterred the attacker in the Pritzwald-Stegmann case, the guard still would have been there to help, which may have resulted in the doctor walking away with his life.

The accountability of management required

Dr. Wong acknowledges that the Victorian Government has increased funding for hospital security since his attack, however, he still worries that the current model in use does not facilitate action.

“Who is responsible for the day-to-day running of a hospital? We don’t have a clear view on that. Is it the board? The CEO? The state government? The federal government?

There are multiple layers of management and a funding model where no-one wants to take responsibility. That’s one of the issues in terms of implementing concrete steps,” he says.

“The policymakers and the people in charge of the day-to-day running of the hospital have to wake up and do something about it.”

A new appreciation for his life

Wong is thankful for surviving the sudden attack with the ability to return to work, as the injuries to his hands could have been detrimental to his career had they been more serious. “You appreciate how precious life is. It can end at any second.”

The road to recovery was long, though. The doctor’s hands and arms were splinted for 6 weeks and he was required to do 6 weeks of physiotherapy to regain his full arm and hand strength. He was unable to walk for three months after the attack.

He realised that he did not want to feel pressured and as if he were on a conveyor belt, speeding down the line, going from patient to patient.

Now, he works in public and private practices but has fewer patients, allowing him to spend more one on one time with each patient that he does have.

“It’s better for me, and a better outcome for the patient,” he said. According to him, the change was welcomed; it gives him more time with his family and reduces his stress levels.

Subsequently, his attack gave him a new perspective. “I feel more empathy towards them,” he said. “I have a deeper understanding of what they’re experiencing, and how disruptive a serious disease condition can be to their lives.”

No sense of security

Despite the good outcomes, Wong has also come to realise that safety is frail and that one can never be too careful when working in a public location.

“As a doctor, even as a nurse working in a large hospital, we often have this false sense of security because there are so many people around,” he said.

“Now I realise that this is not true. All it takes is someone with a small knife and you can be seriously damaged; you can be killed. I accept we cannot totally stop violence, but we can reduce it.”